- Home

- Photo Basics

- Lenses

Picking a lens for nature photography

Choosing your first lens for nature photography can feel like staring at a wall of identical black tubes and wildly different price tags.

Every brand promises tack-sharp wildlife and creamy backgrounds, but no one tells you which single lens will actually help you walk into the woods and come home with photos you’re proud of.

The truth is, you don’t need a backpack full of glass - one well-chosen lens can cover most of what you’ll shoot as a beginner.

In this post, I’ll break down the three lens types that matter most for new nature photographers and help you pick the one that fits how and what you actually like to shoot.

Quick Comparison: Three Lenses for Nature Photography

Here’s a simple overview to help you compare the three main lens types before you dive into the details below.

-

Super-telephoto (approx. 300–600mm)

Typical subjects: Birds, shy mammals, distant wildlife.

What it’s best at: Filling the frame from a distance, with soft, blurred backgrounds.

Main trade-offs: Heavy, more expensive, narrow field of view, often needs faster shutter speeds or higher ISO. -

Macro (approx. 90–105mm true macro)

Typical subjects: Insects, spiders, flowers, fungi.

What it’s best at: Tiny textures and patterns, turning small subjects into big, detailed images.

Main trade-offs: Very close working distance, shallow depth of field, subjects can be easily spooked. -

Wide-angle (approx. 16–35mm, or phone wide)

Typical subjects: Landscapes, wildlife in its environment, dramatic skies.

What it’s best at: Showing the animal in its wider world, not just isolated on its own.

Main trade-offs: You need to be physically close; good lenses can be pricey; can distort if you’re extremely close.

The Super-Telephoto: For Reaching Across the Distance

This is the big one.

The lens that makes people in the park comment on the size of your "camera".

We’re talking about something in the 400 to 600mm range, and its purpose is simple: to bring the distant world right to your eye.

Personally I don't go below 300mm. I only say this from the experience of that mild disappointment when you’re almost close enough, but not quite.

These are the lenses for the shy ones...

Roe deer at Nene Washes at the beginning of January

Roe deer at Nene Washes at the beginning of JanuaryFor the two roe deer that suddenly bolt across a distant field, the kingfisher that won’t let you within twenty paces, or the puffin on a cliff edge.

It allows you to keep a respectful distance, causing no stress to the animal, and yet still capture the glint in its eye or the intricate barring on a feather.

They aren’t feather-light, I’ll grant you that. Carrying one all day is a bit of a workout. But they open up a world of private moments you would otherwise completely miss. For birds and most mammals, this is your magic window.

A Word on the 'Big Guns'

Now, you’ve probably seen them on nature documentaries or in the hands of serious-looking people wrapped in camouflage.

Enormous, often white, lenses that look like they ought to be mounted on a ship. These are the long prime lenses. The tools of the pros.

Their superpower is that they have a very wide-open eye (an 'aperture' in photo-speak) which lets them guzzle in every last scrap of available light. This is why they are so brilliant for capturing that fox at dawn or the owl at dusk.

The trade-off?

Well, they weigh about the same as a small cart. You don't just carry them; you haul them. They really are beasts.

And the other tiny detail is the price. They don’t just empty your bank account; they're more likely to require a second mortgage. Best left to the professionals and lottery winners, I think.

But the distinction between lenses is about more than just cost or size. The choice between a prime and a zoom lens completely changes your approach to photography in the field.

I've written a detailed guide on how to choose the right approach for you.

The Macro: For Discovering the World in Miniature

This one is for getting up close and personal with the tiny wonders.

The bees, the damselflies, or even the impossibly tiny harvest mouse clinging to a stalk of wheat. I’ve crouched in damp grass more times than I care to admit, waiting for a subject to pose just so.

A true macro lens (often around 90-105mm) lets you render these tiny subjects at life-size on your camera’s sensor. The results are pure magic. You see the fine dust of pollen on a bee’s back, the delicate veins in a petal, the alien geometry of a fly's eye. It’s a whole universe right there at your feet. The artist in me adores the patterns and textures to be discovered.

The price for these astonishing shots? Muddy knees and an occasional damp bottom. It’s the uniform of the macro photographer, and well worth it.

The Wide-Angle: For Telling the Whole Story

Now, you might think a wide-angle lens (something like a 16-35mm) is just for sweeping landscapes. And it is! But it’s also a secret weapon for a different kind of wildlife photography.

Instead of isolating an animal, a wide-angle lens places it within its world.

It tells a story. Think not just of the badger, but of the badger emerging from its sett into a forest floor carpeted with bluebells. Not just the rabbit, but the rabbit silhouetted against a dramatic, cloud-filled sunset. It captures a mood, an atmosphere, a sense of place.

Curiously, a good one can be just as expensive as a telephoto lens.

But here’s my trick to save a bit of money to begin with (and weight in your bag): get out your trusty smartphone. For those wide, scene-setting shots where you want to show the sheer scale of the landscape, your phone can often do a brilliant job.

My Final Tip: Just Start with One

You really don’t need all three to begin. That’s a quick way to empty your bank account and fill your bag with heavy glass you’re not sure how to use.

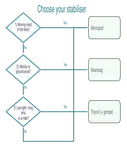

Think about what you love to watch most.

- Is it the birds in the treetops? Start with a super-telephoto.

- Are you fascinated by the insects in the flowerbeds? A macro is your friend.

Pick the one that suits your passion, get to know it intimately, and learn its quirks.

The rest can always wait until Christmas, or your next birthday wishlist.

About the Author

I’m a wildlife photographer who learns on everyday walks. This site is my field notebook: practical photo tips, gentle ID help, and walk ideas to help you see more—wherever you are.

I write for people who care about doing this ethically, who want to enjoy the outing (not stress about the gear), and who'd like to come home with photos that match the memory — or at least the quiet satisfaction of time well spent.

Step Behind the Wild Lens

Seasonal field notes from my wildlife walks: recent encounters, the story behind favourite photos, and simple, practical tips you can use on your next outing.