- Home

- Photo Basics

- Which camera?

Beginner Cameras for Wildlife Photography (UK Guide)

My first prize-winning wildlife shot - a pin-sharp mayfly, all fragile wings and fine veins, wasn’t taken with a high-end body, but with a scuffed little beginner wildlife camera and a well-used macro lens.

That image didn’t win because I’d spent thousands; it won because the camera was good enough for what I needed it to do.

If you’re standing in a camera shop (or scrolling online) wondering if you have to blow your savings to get “real” wildlife photos, the answer is no.

In this guide, I’ll show you how to choose a camera that fits your budget, your subjects, and your style - without getting lost in specs or marketing hype.

Understanding Camera Types

For wildlife photography, the camera world really boils down to three main types. Each feels different in your hands and offers its own way of seeing and capturing the natural world.

The DSLR: The Sturdy Workhorse

The DSLR (Digital Single-Lens Reflex) has been the standard for years, and many wildlife photographers still rely on it.

When you look through the viewfinder, a system of mirrors shows you exactly what the lens is seeing.

Why DSLRs are appealing:

- Tough and reliable

- Huge second-hand market for bodies and lenses

- Optical viewfinder shows the real scene with no lag

Main drawback for wildlife:

That mirror flipping up and down makes a distinct clack with every shot. For a cautious roe deer or nervous bird, that might be just enough noise to spook it.

The Mirrorless: The Silent Observer

This is the new standard, and after years with DSLRs, I’ve switched.

The mirror is gone. The sensor is always exposed to light, and the image appears on a tiny electronic screen in the viewfinder.

Key advantages:

- What you see is what you get: your exposure and colour settings are shown in real time

- Silent electronic shutter: you can shoot without making a sound, which is invaluable when you’re a few feet from your subject.

- Advanced autofocus: many systems can recognise an animal’s eye and lock onto it automatically (and yes, it really does work).

The Bridge Camera: The All-in-One Wonder?

A bridge camera is the sensible shoes of the photography world.

It’s an all-in-one camera with a fixed lens that covers a huge zoom range, from wide-angle to super-telephoto. For a beginner, it’s a practical and affordable way to start.

What bridge cameras offer:

- One body, one lens, huge zoom range

- Switch from a distant kestrel to a bee on a thistle without changing lenses

- Lightweight and uncomplicated, ideal for learning

The sensors are usually smaller, so they can struggle in very gloomy light. But their sheer versatility makes them a great tool while you are deciding whether you want to take wildlife or nature photography further.

What to Look for in a Wildlife Camera

Your camera doesn’t need to be the latest and greatest. But a few key features will make life in the field (or the back garden) much easier.

Fast Autofocus

Wild animals rarely hold a pose. You want a camera that:

- Locks focus quickly

- Tracks moving subjects without hunting back and forth

Fast, reliable autofocus helps you grab those blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moments.

A Decent Burst Mode

Burst mode lets you fire off a rapid series of shots with one press of the shutter, without the camera freezing while it saves.

Think of it as insurance: more frames mean a better chance of catching the perfect wing position, leap, or glance to camera.

Good Low-Light Performance

Wildlife loves to appear at dawn and dusk, when the light is either magical or maddening.

Look for a camera that:

- Handles higher ISO without turning everything into mushy noise

- Keeps details and colour even when the light is low

A camera that isn’t afraid of the dark is a real bonus.

Weather Resistance

Because, let’s be honest, British weather couldn’t care less about your plans.

A bit of weather sealing means your camera is more likely to shrug off:

- Drizzle

- Mist

- The odd unexpected shower

You’ll worry less about the gear and concentrate more on the wildlife.

The Great Muddle of Megapixels and Sensors

When I started, I spent far too long fretting about whether I needed a full-frame camera or if my little crop-sensor was good enough.

Here’s the short version: both are perfectly fine for wildlife.

Full-Frame vs Crop Sensor

The main practical difference is how tightly your lens frames the scene.

On a crop-sensor camera:

- A 300mm lens behaves more like a 450mm lens in terms of how close it feels.

- Your subject fills more of the frame without you moving an inch.

For wildlife, where you often can’t just step closer, that extra apparent reach is a genuine bonus. It’s a bit of a cheat, really—but a very useful one.

Megapixels: Less Important Than You Think

And megapixels? They matter far less than most marketing would have you believe.

My prize-winning mayfly was captured on a 16-megapixel camera. What matters more is the quality of those pixels - how clean, detailed and well-handled the image is.

That said, having more megapixels does give you extra flexibility:

- You can crop more aggressively and still end up with a usable image.

- It’s handy when that lovely heron shot includes a bit too much boring pond, and you want to refine the composition afterwards.

The perfectionist in me does enjoy that freedom to tidy up the frame, but it’s the final image that counts, not the megapixel bragging rights.

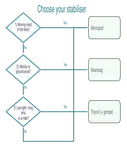

So, How Do You Choose?

After years of being asked for camera advice, I’ve landed on this:

The best camera is the one you’ll actually pick up and use.

From there, it depends on what kind of beginner you are.

If You’re Curious but Cautious: Go Bridge

If you’re interested in wildlife photography but wary of the cost, a bridge camera is the simplest way in.

It’s photography with the training wheels on, in the best possible sense:

- One body, one lens, huge flexibility

- Wide landscapes one moment, distant deer the next

- No worrying about which lens to pack or swap

You can concentrate on learning how to see, not how to shop.

If You Love a Solid, Classic Feel: Go DSLR (Especially Used)

If you’re drawn to the heft and bright optical viewfinder of a DSLR, don’t let anyone tell you they’re obsolete.

Some of my most treasured shots came from cameras that are now considered ancient history.

And don’t overlook the used market:

- A three-year-old “flagship” will still make fabulous images

- You’ll get robust build and great controls for a fraction of the original price

- Wildlife doesn’t care how old your camera is, it cares about your patience

If You’re Ready to Grow: Go Entry-Level Mirrorless

If you’re keen to grow into the hobby, an entry-level mirrorless is probably the sweet spot.

You’ll get:

- A system you can expand with new lenses over time

- A silent shutter that’s a real asset, from your first garden robin to your hundredth wary heron

- Modern features like animal-eye autofocus that quietly handle some of the technical fuss for you

The technology is moving forward quickly, and mirrorless is where most of that progress is happening.

The Only Wrong Choice Is Not Using It

Whatever you choose, don’t agonise over ticking every box on a spec sheet.

Pick a camera that feels friendly in your hands, then get out there and start looking.

You’ll be amazed at what you see once you start paying attention.

Further Reading

Getting Started:

How to Start Wildlife Photography - Planning your first shoots and spotting wildlife without overwhelm

Wildlife Photography Tips for Beginners - Essential techniques that will help you get great photos straight away

Camera Skills:

How to Change Camera Settings - Step-by-step guide to adjusting ISO, shutter speed, and aperture

Getting into Wildlife Photography - The right gear, techniques, and tips for capturing stunning wildlife shots

Golden Hour Photography - Capturing wildlife during that magical time when the light is warm and soft

About the Author

I’m a wildlife photographer who learns on everyday walks. This site is my field notebook: practical photo tips, gentle ID help, and walk ideas to help you see more—wherever you are.

I write for people who care about doing this ethically, who want to enjoy the outing (not stress about the gear), and who'd like to come home with photos that match the memory — or at least the quiet satisfaction of time well spent.

Step Behind the Wild Lens

Seasonal field notes from my wildlife walks: recent encounters, the story behind favourite photos, and simple, practical tips you can use on your next outing.