- Home

- Wildlife in the UK

- Norfolk

How a Failed Quest for a Swallowtail Butterfly Taught Me to Really See

The Obsession Begins

For years, I dreamt of seeing the rare British Swallowtail butterfly. It wasn’t just a wish; it became a personal quest, a mission that focused my love for nature and photography on a single, magnificent prize.

Their only UK stronghold is the fens and broads of Norfolk, a manageable distance from our home in Cambridgeshire.

And so, my husband and I planned a weekend escape, my hopes pinned on finding this elusive creature.

I now realise I had fallen into the classic beginner’s trap: the checklist.

That checklist wasn't just a list; it was a shield against feeling foolish. My photography felt the same way. 'Getting the shot' was the final, most important tick-box. It would prove I’d earned my place here.

My goal was singular, my focus a pinprick. I wanted to see a Swallowtail Butterfly, photograph it, and tick the box.

Nature, however, had a different lesson in mind.

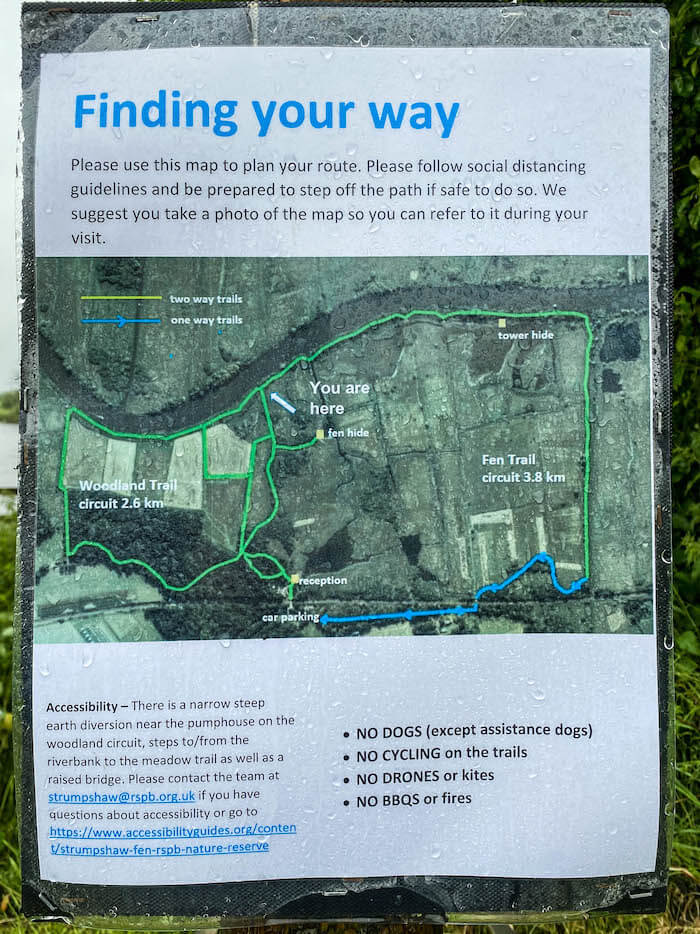

A rather wet Strumpshaw Fen map

A rather wet Strumpshaw Fen mapWhen Nature Says NO!

Our first trip, at the end of May, was a washout.

As soon as we arrived at Strumpshaw Fen, the leaden grey skies released a torrent of water.

I remember the volunteer in the visitor centre giving us a sympathetic look. "You won’t see them today," he said, "they hate the rain and wind."

I felt the day's optimism drain out of me, leaving a cold, damp feeling that had nothing to do with the rain.

It’s a humbling feeling when you realise nature doesn’t owe you anything, no matter how carefully you’ve planned.

As we returned to our room drenched and shivering, I felt a pang of guilt for dragging my husband on what had become my ultimate fear: the classic 'wasted, frustrating weekend'.

The only Swallowtail we saw that year was on a large soggy poster.

The only Swallowtail we saw in 2021

The only Swallowtail we saw in 2021Gifts In Disguise

But even in our failed quest, there were gifts.

While the butterflies remained hidden, for now, the Marsh Harriers didn't seem to mind the weather, and I also watched Cuckoos and Jays go about their business.

These were moments of unexpected beauty, yet my mind was still on the prize I’d missed. I was looking, but I wasn't truly seeing.

Female Marsh Harriers

Female Marsh Harriers

We Return with New Eyes

Fast forward one year, and we were back in Norfolk for a long weekend in June.

This time, the weather was perfect: hot, sunny, and still. And something in my approach had shifted.

The sting of last year’s disappointment had taught me to loosen my grip. It wasn't just the butterfly checklist I let go of; it was my rigid approach to photography, too.

I was tired of taking pictures that felt like mere proof I was there, snapshots that never captured the feeling of a place.

This time, my goal was simpler: to be present, and to let what I saw, truly saw, guide the camera, not the other way around.

We started at Strumpshaw Fen again, and this time, I was glad I’d learned to pack for the terrain, not just the forecast. My waterproof boots felt like a badge of experience earned from the previous year's soaking.

We saw green-eyed Norfolk Hawker dragonflies resting on reeds.

Norfolk Hawker at rest

Norfolk Hawker at restWe watched a Great Crested Grebe with three tiny babies on its back, and from a hide, I spotted my first-ever Chinese Water Deer, its comical tusks and teddy-bear ears a complete surprise.

And then, as we walked past the historic Doctor's House, it happened.

The Moment of Discovery

Not with a grand announcement, but as a quiet flutter in the dappled sunshine among the garden flowers. Two of them.

I felt my breath catch. For a moment, I forgot I was even holding a camera.

The Swallowtail’s wings weren't just yellow; they were the colour of pale lemon silk, so thin the sunlight seemed to shine right through them.

As soon as I saw them, my old habits flared up. My camera came up, and I fired off a few shots. They were really just snapshots. Proof.

The butterfly was partly lost in a messy background, a picture that screamed 'I was here!' more than 'look at this beautiful scene.' It was the visual equivalent of ticking a box, and while I treasured the memory, the photo itself was a reminder of the way I was trying not to see.

But to me, in that moment, it was a priceless start.

My photos were really just snapshots, the kind of disappointing pictures I was so used to taking. The butterfly was partly lost in a messy background, screaming 'beginner' to anyone who looked. But to me, in that moment, they were priceless.

My photos were really just snapshots, the kind of disappointing pictures I was so used to taking. The butterfly was partly lost in a messy background, screaming 'beginner' to anyone who looked. But to me, in that moment, they were priceless.Gracefully, they moved from flower to flower. This wasn't just a sighting; it was an arrival. It felt as though the prize had appeared only after I had stopped chasing it so desperately.

Our visit to Hickling Broad Nature Reserve the next day confirmed this lesson.

We arrived early to near-solitude and almost immediately, a Swallowtail darted across our path. Too quick for a photo, but a wonderful hint of what was to come.

Hickling Broad Visitor Centre from the car park

Hickling Broad Visitor Centre from the car parkIt was here I learned that the butterfly’s entire existence hangs on a single, humble plant: milk parsley.

It's the only food for its caterpillars, and its managed presence in Norfolk is the sole reason the Swallowtail survives here.

This fact struck me with profound weight; conservation isn't an abstract idea, but the gritty, hands-on work of ensuring one plant can thrive.

At one of Hickling's thatched bird hides, we met a woman who’d spotted Swallowtails nearby.

Following her direction, we found one posing perfectly.

Its red-orange spots glowed, and the blue patches sparkled in the sun. My heart was thumping, but I slowed my breathing.

Building My Skills

A year ago, I would have just zoomed in, trying to capture the butterfly as a specimen, another item for my list.

But now, I was seeing the whole scene: this small, perfect creature resting in a world of soft light and swaying reeds. I wasn't there to just document an insect; I was there to capture a feeling of tranquility.

And to do that, I knew I had to do something I used to be afraid to touch.

I deliberately reached for the aperture dial. By choosing a wide opening, I could let the background melt away into a soft, dreamy blur, making the butterfly the focus of its quiet world.

The click of the shutter was deliberate, satisfying.

I'd captured not just an image, but the feeling of a two-year journey culminating in a single, tranquil moment.

It was the first photo I was genuinely proud to share, without making excuses for it.

Swallowtail in an interesting pose!

Swallowtail in an interesting pose!Your Blueprint for Success

If you wish to go on your own Swallowtail adventure, I hope my story helps you bypass the frustration and go straight to the joy.

From my experience, you’ll have a better chance at Hickling Broad, though both reserves are magical.

Aim for late May to mid-July.

But more importantly, I encourage you to do what I finally learned to do: swap your 'what' checklist for a 'how' checklist.

'How can I use my camera to capture the feeling of the light today?' or 'How will I feel if I am truly present and just listen for five minutes?'

This simple switch changes everything, because it’s a game you can win every single time you step outside.

A singing Willow Warbler

A singing Willow WarblerMy old list was a recipe for failure: 'See a Swallowtail.' My new list was a recipe for success, because I was in control of it.

For me it turned out that the real quest wasn’t for a butterfly. It was a journey to learn a new way of seeing.

The most precious moments of my trip, the deer, the otter we spotted on the final day, the warbler singing from a treetop, were all gifts I received when I opened my eyes to everything, not just the one thing I thought I wanted.

That is the true magic: to stand in nature, not as a hunter with a list, but as a quiet guest, ready to be surprised.

About the Author

I’m a wildlife photographer who learns on everyday walks. This site is my field notebook: practical photo tips, gentle ID help, and walk ideas to help you see more—wherever you are.

I write for people who care about doing this ethically, who want to enjoy the outing (not stress about the gear), and who'd like to come home with photos that match the memory — or at least the quiet satisfaction of time well spent.

Step Behind the Wild Lens

Seasonal field notes from my wildlife walks: recent encounters, the story behind favourite photos, and simple, practical tips you can use on your next outing.