- Home

- Photo Basics

- Camera Settings for Wildlife Photography

Camera Settings for Wildlife Photography Beginners

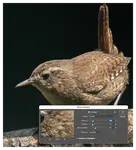

I was shuffling along the edge of a hawthorn hedge, trying to be quiet, when a wren practically exploded out of the leaves.

The light was doing that gorgeous, honeyed thing it does in late afternoon, and I couldn't resist capturing the moment. But then I looked at my camera screen. The photo was... well, it was dull. Just a brown smudge in a tangle of grey sticks.

It’s heartbreaking, isn't it? You feel that rush of adrenaline, but the camera doesn't know what you're feeling; it just records a bunch of light data.

The secret isn't "better gear". It's learning how to translate what your heart sees into settings the camera understands. You have to tell it exactly where the light matters and what story you're trying to tell.

It's a bit of a dance, and I still trip over my feet constantly, but when you finally bridge that gap, it's pure joy.

This page aims to help you achieve that feeling.

The Field Framework That Closes the Gap

I’ve found that a simple way to close that gap is to decide what matters most to you before you touch the dials. Once you know what you're trying to capture, your camera settings will support that choice rather than fighting against it.

Most setting guides explain ISO, shutter speed, and aperture separately. In the field, that’s exactly how you end up chasing your tail.

Instead, this repeatable workflow translates “what you felt” into “what the camera needs”:

You don’t need to chase moments. You need to notice them — and choose the setting that protects what mattered.

Pre-Visualize → Prioritise → Validate

Pre-Visualise: What’s the photo meant to say? (sharp wings, soft mood, clean background, warm light)

Prioritise: Set the one thing you don’t want to compromise:

- Motion → shutter speed first

- Separation / story → aperture + your position next

- Brightness / noise → ISO last

Validate: Don’t trust the “pretty” look on the back of the camera. Check focus + histogram + highlight warnings, then adjust one thing.

Choose your moment (jump to the scenario that fits)

Birds in flight

Start with shutter speed, then let ISO do the heavy lifting.Dappled woodland light

Background and angle matter as much as exposure.Bird in shade, bright background

Your camera will “average” the scene unless you take the lead.Dusk wildlife

Protect sharp eyes first; accept a little noise.

Why the Scene Felt Three-Dimensional (and the Photo Didn’t)

Your eyes don’t just see — they interpret. Your brain quietly picks the subject, ignores clutter, and smooths out brightness extremes.

A camera is more literal, and it records everything with the same honesty.

- Dynamic range: You can see detail in bright sky and deep shade at once. A camera often has to choose.

- Selective attention: You naturally ignore the messy branch behind the robin; the camera doesn’t.

- Depth perception: Two eyes + constant micro-refocus creates depth. A photo is one plane unless you create separation.

- Motion: Your brain “stabilises” movement; the camera freezes or blurs based on shutter speed alone.

- Colour mood: Your eyes adapt to warm sunrise and cool shade; the camera may try to neutralise it.

So when a photo feels flat, it’s often not a single “wrong setting.” It’s that the camera guessed the priority — and guessed differently than you felt.

Pre-Visualize in 10 Seconds (Before You Change Anything)

This is the little pause that makes the rest easier. Before you adjust settings, try asking:

- What’s the moment? (a look back, a wing stretch, a chase, a quiet stillness)

- What’s the feeling? (crisp detail, soft intimacy, dramatic silhouette, warm glow)

- What’s most likely to spoil it? (motion blur, missed focus, busy background, blown highlights)

Then choose one “non-negotiable.” Something like:

- “I want the eye sharp.”

- “I want the wings crisp.”

- “I want a calm, soft background.”

- “I want to keep detail in those bright feathers.”

That one choice tells you where to start.

Prioritize: One Decision at a Time (So You Don’t Chase Your Tail)

Outdoors, things change quickly: a cloud moves, the animal turns, the background shifts as you take one step. I’ve found it helps to set settings in a practical order: motion first, then separation, then brightness.

If motion is the story, start with shutter speed

If your biggest disappointment is “it looked sharp when I took it,” you’re usually fighting shutter speed. Choose a starting point that matches movement, then adjust from there.

Gentle starting points (you’ll adjust for your light and your lens):

- Perched birds / calm animals: 1/250–1/500

- Feeding / head movement: 1/500–1/1000

- Running mammals: 1/1000–1/2000

- Birds in flight: 1/1600–1/3200

- Intentional motion blur (panning): 1/30–1/125 (this one needs practice)

If those shutter speeds sound “too fast for the available light,” don’t worry — that’s where aperture and ISO step in.

One small note from the long-lens end of wildlife photography: the longer your focal length, the more a ‘perfectly reasonable’ shutter speed can start to feel a little marginal — especially if you’re handheld.

In those moments, I’ll often protect shutter speed first, and let ISO rise to support it.

Handheld at 600mm from inside a hide: f/11, 1/800, ISO 6400 (0 EV). At long focal lengths, I’ll often take a little noise over a shutter speed that’s just a touch too slow.

If the photo feels busy, work on separation next

Aperture helps, but it’s only one part of separation. On walks, your position can matter just as much as your f-number.

To help the subject stand out, you might try:

- Increase the distance behind your subject: a bird on a branch with open sky behind will look calmer than one backed by tangled twigs.

- Shift your angle: one step left or right can turn chaos into a clean backdrop. Use a longer focal length if you have it: it tends to soften and simplify backgrounds.

- Open the aperture a little: f/4–f/6.3 is often a friendly range for wildlife (wide enough for blur, not so wide you lose too much depth).

- Watch the “too thin” trap: close up, very wide apertures can make the eye sharp but the beak or body soft.

If a photo looks flat, I’ll often try a tiny change of viewpoint before I change anything else. It’s the most underrated “setting” you have.

Left: A little distance behind the bird gives a soft, quiet background — it’s one of the simplest ways to make a subject feel three-dimensional.

Right: A clean patch of sky can work just as well. The background is simplified, but you may need a small exposure nudge to stop the bird going dull.

Then use ISO to pay for the choice you just made

Once shutter speed and aperture are supporting the moment, ISO is how you bring the exposure where it needs to be.

- If your shutter speed is slipping too slow, raise ISO (especially for moving wildlife).

- If noise is creeping in, see if you can open aperture a touch or find cleaner light by changing position — then lower ISO.

- If your camera allows it, Auto ISO can be surprisingly helpful on walks: you pick shutter + aperture, and the camera rides ISO as the light changes.

A lot of wildlife photographers (especially when things happen quickly) enjoy Manual exposure + Auto ISO because it keeps motion and depth of field steady while the camera handles the brightness housekeeping.

Two settings people forget: focus and drive mode

Sometimes the “flat” feeling is simply a missed focus moment — the background is sharp, the animal is a touch soft, and the whole frame loses life.

You might experiment with:

- Continuous/Servo AF for moving subjects, Single/One-shot for still ones

- A smaller focus area/point when there are branches in the way

- Burst/continuous drive for unpredictable moments (it helps you catch the exact head angle)

- RAW if you can — it gives you more room to bring back the tones you felt in the scene

Metering + Exposure Compensation (So the Camera Stops “Averaging” Your Wildlife Scene)

On a walk, the light is rarely simple. A bird steps from shade into sun, a fox sits under a hedge with bright grass behind, a white swan drifts across dark water.

Your camera’s meter tries to make the whole scene look like a mid-tone — which is often why the file comes out a little dull, or your subject looks lifeless.

A simple way to think about metering is this: the camera is guessing what “normal brightness” should be.

Exposure compensation is how you gently say, “Not this time — I want it a little brighter,” or “Hold on — keep those highlights safe.”

The three metering modes (and when they’re useful)

- Matrix / Evaluative (best everyday choice): The camera looks at the whole frame and makes a balanced guess. Good for most wildlife walking moments.

- Center-weighted: Still considers the whole frame, but cares more about the middle. Helpful when your subject is central and the edges are bright or messy.

- Spot metering: Measures a very small area. Can be brilliant for backlit or high-contrast scenes — but it’s easy to fool if your spot slips onto sky or a white feather while the animal moves.

If you’re not sure, start with Evaluative, then use exposure compensation + validation (histogram/blinkies) to fine-tune.

Exposure compensation, explained gently

Exposure compensation is just a small nudge: + makes the file brighter, – makes it darker. It’s most useful when the camera’s “average” guess isn’t matching what you’re actually trying to photograph.

Common moments where compensation helps on wildlife walks:

- Bright scenes (snow, pale sand, bright sky, white birds): the camera often darkens too much → you’ll often prefer a + nudge.

- Dark scenes (deep woodland, dark fur filling the frame): the camera often brightens too much → you may prefer a – nudge.

- Backlit subjects (sun behind the animal): the camera protects the bright background and your subject goes flat → you’ll often want + for the subject, then validate highlights.

Little “starting nudges” you can try (then check histogram/blinkies)

- White bird in bright sun / snow scenes: try +0.7 to +1.7

- Dark animal filling the frame / deep shade: try –0.3 to –1.0

- Subject in shade with bright background: try +0.7 to +1.7 for the subject (and accept the background may go bright), then validate highlights

- Backlit silhouette (you want a true silhouette): try –0.7 to –2.0 to keep the shape clean

These aren’t rules — just gentle starting points. Your histogram and highlight warnings will tell you the truth in your light.

Here are two hare moments where +2/3 EV helped. They’re a good reminder that the camera often plays it safe in bright scenes — and your subject can end up looking a little dull unless you take the lead.

On my Canon EOS 5D Mark II, I didn't have a histogram in the viewfinder, so any check happens in playback — just a quick glance, then back to the moment.

Left: Even in action, a bright ground can pull the exposure down and leave the hare looking flat. This frame was f/5.6, 1/1000, ISO 1000, +2/3 EV at 400mm (EF 100–400mm). If it still looks a touch dull, I’ll add a little more exposure and then check playback.

Right: Backlight feels luminous to our eyes, but the camera often ‘averages’ the brightness and turns the subject into a dark cut-out. This was f/5.6, 1/3200, ISO 1000, +2/3 EV at 400mm (EF 100–400mm). A quick playback check helps you keep the sparkle without losing the hare.

A few practical ways to meter for wildlife without fuss

- If the subject is steady: you might use spot metering on the animal, tap AE-L / exposure lock if your camera has it, then recompose.

- If the subject is moving: it’s often easier to stay on evaluative metering and use exposure compensation (spot metering can slip off the subject mid-action).

- If you use Manual + Auto ISO: exposure compensation usually tells the camera to raise/lower ISO (handy when light changes quickly).

- If you shoot RAW: you often have a bit more room to recover shadows/highlights — but it’s still kinder to protect important highlights in-camera.

After you make a compensation change, take one frame and do the quick check: zoom in on the eye, then blinkies + histogram. If you’re losing detail where it matters, adjust one step and try again.

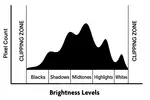

Validate: A Quick Check That Saves Disappointment at Home

The back-of-camera preview is affected by screen brightness and the light around you.

In bright daylight, a too-dark file can look fine.

In shade, a good file can look dull. A quick validation habit helps.

My “walk-friendly” validation loop

-

Zoom in on the eye (or the sharpest detail)

- If it’s soft, adjust your focus approach first.

- Check highlight warnings (“blinkies”) if your camera offers them

-

Glance at the histogram

- Pressed hard to the right can mean lost highlight detail.

- Piled on the left can mean crushed shadows.

- Adjust one thing (often ISO or exposure compensation), then shoot again

I try to keep validation calm and quick: focus, histogram, one adjustment — then back to watching the animal.

Field Scenarios (Step-by-Step, With the Reasoning)

Scenario A — Birds in Flight (when sharp wings matter most)

On windy days, birds can look as if they’re almost hovering — beating hard just to hold their line. It’s a lovely thing to watch, and it’s also a reminder that “birds in flight” isn’t only about speed. It’s about how steady the whole moment is, including gusts and sudden changes of direction.

Try this approach:

- Pre-visualise: “I want crisp wings and a sharp eye.”

- Shutter first: choose a fast starting point (often 1/1600–1/3200 for small, fast birds; a little slower can work for larger birds or calmer flight).

- Aperture next: open enough for light, but don’t be afraid to stop down a touch if tracking is tricky (a little extra depth can be forgiving).

- ISO last: let ISO rise to protect the shutter speed you chose (Auto ISO can be very helpful here)

- Focus/drive: Continuous AF + burst; keep your focus area where you can reliably hold it on the head/upper body.

Photo moment: After a short burst, I’ll take a quick look in playback and zoom in on the eye. If it’s not quite there, I’ll usually nudge the shutter speed up first — windy days add their own wobble — and only then change my focus area.

Ethics note: If a bird changes direction or calls repeatedly, I treat that as a sign to back off and let it settle.

Try-this-next-time: Practice on common birds first (gulls, pigeons, crows). They’re generous teachers.

Puffin in a gale: on an extremely windy day the birds were almost hovering and fighting to move forward. I still kept a fast shutter (1/1250) to hold detail in the wings, used f/9, and the light was bright enough that ISO stayed low (ISO 200) (Canon 7D Mark II at 400mm).

Scenario B — Dappled Woodland Light (when everything looks “muddy”)

Under trees, light arrives in patches. Your eyes handle it beautifully; the camera often produces a file that feels grey or cluttered.

Try this approach:

- Pre-visualise: “I want a calm subject and a quieter background.”

- Separation: shift your angle so the animal sits against a darker, more distant background

- Aperture: open a little (f/2.8–f/5.6 if available)

- Shutter: keep it safe for small movements (1/500–1/1000)

- ISO: lift ISO to support shutter speed

Photo moment: If a deer looks up into a brighter patch for a second, that’s often your “ordinary magic” frame. I’ll shoot a short burst, then check focus quickly.

Ethics note: In woodland, it’s easy to step closer without realising. I try to let the animal set the distance.

Try-this-next-time: Before you raise the camera, take one slow step sideways and look at the background. Often that’s the whole fix.

Scenario C — Subject in Shade, Bright Background (the “averaging” trap)

This is a common one on walks: a bird in shade with bright sky behind, or an animal under a hedge with sunlit grass beyond.

The camera tries to “average” the scene and your subject ends up dull.

Try this approach:

- Pre-visualise: The animal is the story; the background can be less detailed.

- Shutter: Keep it safe for movement first

- Aperture: Open enough for separation

- ISO / exposure: Raise exposure for the subject, then validate highlights with blinkies + histogram

RAW: Helpful here, because it gives you more room to recover tones

Photo moment: I’ll take one frame, check whether the subject has detail, then decide what I’m willing to lose — sometimes a brighter background is perfectly fine if the animal looks alive and present.

Ethics note: Backlit scenes can tempt us to keep repositioning. If the animal is resting, I’ll keep my movement slow and minimal.

Try-this-next-time: When you spot a bright background, see if you can move so the subject has a darker backdrop instead. It’s often easier than “fixing” exposure alone.

Scenario D — Wildlife at Dusk (when mood matters and focus gets tricky)

At dusk, the light feels beautiful and soft — and it’s also where focus and motion blur quietly sneak in.

Try this approach:

- Pre-visualise: “Sharp eye, gentle mood.”

- Aperture: as wide as is sensible for your lens

- Shutter: choose the slowest you can get away with for the animal’s movement (often 1/500+ if alert)

- ISO: accept a higher ISO rather than a too-slow shutter speed

- Validation: zoom-in focus check is especially important here

Photo moment: If the animal pauses, I’ll take a couple of frames, check the eye at 100%, then carry on walking rather than staying fixed in place.

Ethics note: Low light is when wildlife is often busiest. I avoid flash, keep my distance, and let the moment pass if it feels sensitive.

Try-this-next-time: Practise your dusk settings on a stationary subject first (a signpost, a tree trunk). It helps you learn what “safe sharp” looks like on your camera.

A Calm Practice for Your Next Walk

If you try one thing this week, try the workflow once per outing — just once — and notice how it changes your keepers.

- Pre-visualise the feeling (motion / separation / mood)

- Set the priority in that order

- Validate focus + histogram

- Then go back to walking slowly and watching

Quiet walks. Better wildlife photos.

Back to: Getting Into Wildlife Photography

About the Author

I’m a wildlife photographer who learns on everyday walks. This site is my field notebook: practical photo tips, gentle ID help, and walk ideas to help you see more—wherever you are.

I write for people who care about doing this ethically, who want to enjoy the outing (not stress about the gear), and who'd like to come home with photos that match the memory — or at least the quiet satisfaction of time well spent.

Step Behind the Wild Lens

Seasonal field notes from my wildlife walks: recent encounters, the story behind favourite photos, and simple, practical tips you can use on your next outing.